Yesterday afternoon, I put out a forecast on our Instagram page for the impending snowstorm in the Mid-Atlantic region which occurred overnight last night. The forecast I made for our area was 2 to 5 inches of snow accumulating on the ground between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. What ended up happening was the snow started relatively on time but lasted a shorter than initially thought and only amounted to about an inch on the ground here in College Park. I could look outside from my apartment window early this morning and see that the blades of grass were not even fully covered, which meant the forecast was considered a “bust”, or in other words, the storm did not quite live up to expectations. So, what exactly went wrong?

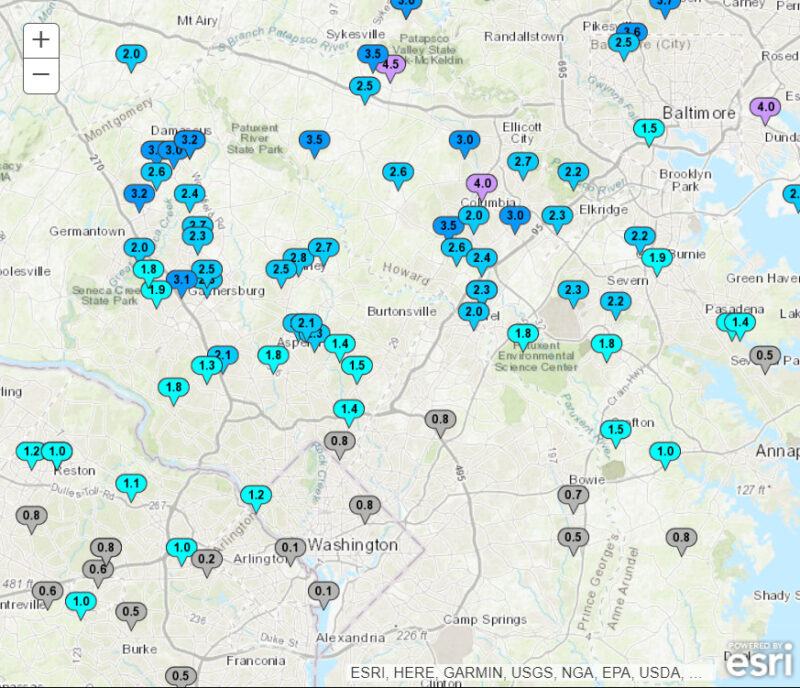

To start, it should be noted that areas not too far to the north of College Park did see snow totals from 2 to 4 inches, such as in Laurel, Germantown, and Columbia. We just happened to be just outside the southern fringe of those amounts.

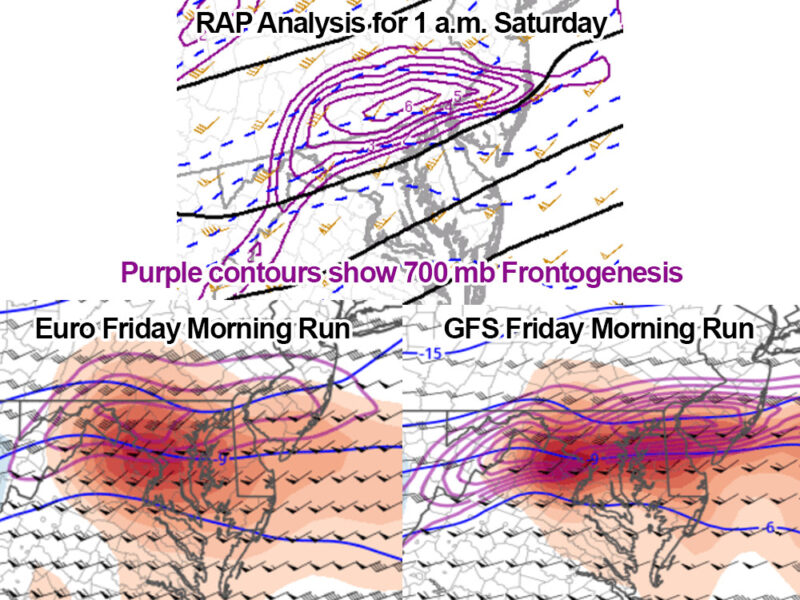

Computer model guidance coming out from the Friday morning model runs were promising in terms of some decent snowfall in the Washington D.C. metro region. The ECMWF, or “Euro model” which is typically regarded as the most accurate weather model, showed snow totals solidly within the 2-to-4-inch range in the region, including here in College Park. The other major global model, the GFS aka the “American model”, was similar, as were a couple of higher resolution models such as the NAM and HRRR. Many of these models had also trended higher with the snow totals since the day before, giving a little more confidence in the higher totals.

Another thing to note is that though the snow was only expected to occur for a few hours overnight, the snowfall rates were expected to be heavy, potentially reaching an inch per hour or more at times. One of the reasonings behind this prediction was due to a meteorological phenomenon known as frontogenesis. Without getting too technical, areas with a greater magnitude of frontogenesis often correlate with higher snowfall rates during winter storms. On Friday morning, strong frontogenesis was being modeled to take shape across central and northern Maryland as the snow came through Saturday morning. So, despite the short lifespan of the storm’s duration, it was thought that heavy snowfall rates could make up for it and even potentially make the storm overperform. However, what really happened was that the band of strongest frontogenesis set up a little farther north than anticipated, being placed primarily over southern Pennsylvania. Parts of eastern Pennsylvania and central New Jersey got walloped with snow as a result, with up to a foot of snow in some places.

These little jogs to the north or south can make all the difference for snow in a single location, and it may be one of the main reasons why some places just 10-20 miles north of here did fall within the expected range whereas we did not. Though, this was not the only reason for underperformance.

We reached a high of 48 degrees Friday afternoon on the Atlantic Building roof, which already should have raised some red flags. Those temperatures plus solar heating of the ground during the day can make it difficult for snow to stick to the ground, even several hours after sunset. By midnight, the station on the roof still read 40 degrees, which meant it would be very difficult for snow to stick right away and there was still some rain mixed in at the beginning as well. Even as snow started to fall at a steady pace, the temperature never quite got completely below freezing at the surface, meaning the snow-to-liquid ratio was not going to be as high as initially forecast. Snow-to-liquid ratios determine how much snow can fall out of the equivalent amount of liquid water (e.g. a 10:1 ratio means 10 inches of snow may fall for every 1 inch of equivalent rainfall). Warm air near the surface coupled with some mid-level dry air, as well as weaker frontogenesis than forecast, helped limit the snow-to-liquid ratio to a lower one than expected. Not only this, but the snow ended soon after 3 a.m., which was much earlier than previously thought.

Friday evening model runs did reflect a downtrend in the snow totals for our area, but by then the forecast had already been put out. Ultimately, winter storm setups like this one can have very fine margins of error and a matter of miles or just enough warm air can make the difference between an overperformance and a bust. Weather forecasting computer models have come a long way in recent decades, but they are not perfect. It is a game of constant learning, and this one was for sure a learning experience.