Perhaps you’ve heard the news by now. Winter is coming (back). We’ve got cold air on the way but of more importance and excitement, we’ve got a shot a real snowstorm early next week. Let’s breakdown the setup and potential scenarios.

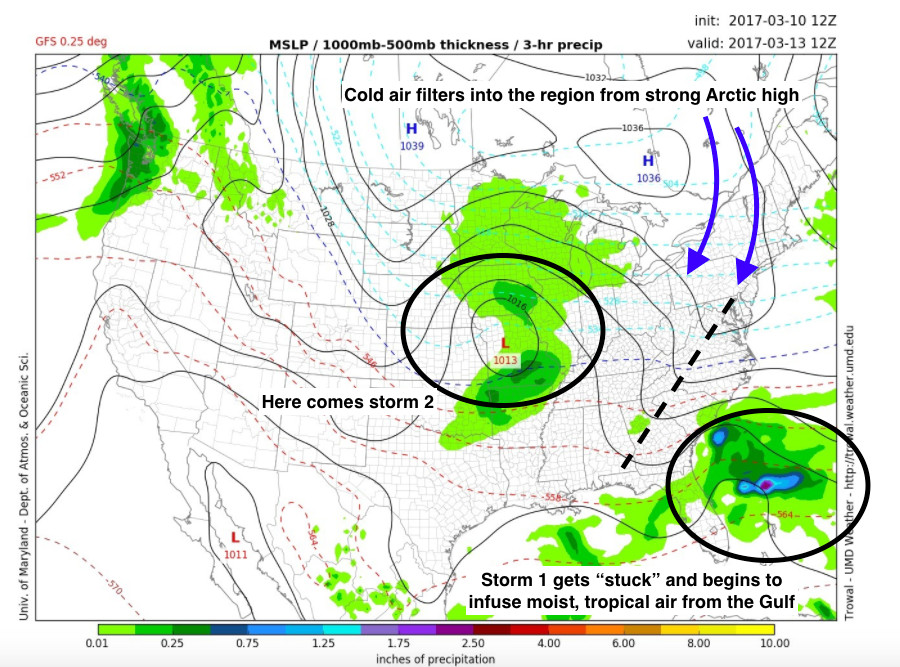

Surface pressure and precipitation. (Via GFS)

The setup

Things are certainly about to change in the temperature department. Cold air, originating in western Canada, is filtering into the mid-Atlantic this afternoon. You’ll note its arrival by the gusty winds expected by this evening. With an Arctic air mass in place, temperatures this weekend will be a good 10-15 degrees below normal for this time of year. We’ll call that ingredient number 1.

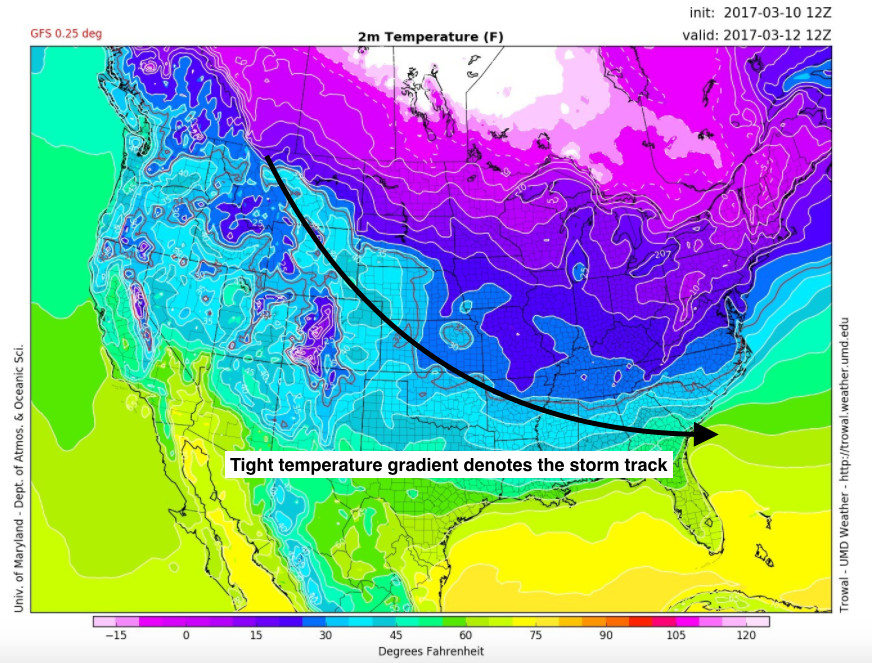

Forecasted surface temperatures for Sunday at 8am. (Via GFS)

The second ingredient comes in the form of an active storm track. Battle lines will be drawn, with the cold Canadian air mass pushing up against a warm Gulf of Mexico air mass. Along that line of demarcation, two pulses of energy will move in quick succession from the Montana down towards the southeastern United States. The first of these disturbances misses wide right on Sunday, shunted to the south by the aforementioned area of high pressure. Things get a little complicated after that.

Surface pressure and precipitation for Monday morning. (Via GFS)

The first storm system is not allowed to exit to the Atlantic as per usual. The culprit preventing this movement is a strong area of high pressure located over the western Atlantic. Think of it physically as a big rock in the middle of a river, where the river flow gets altered because of the rocks presence.

This doesn’t stop the flow from continuing further upstream, where the second storm system will be quickly on the heels of the first one. Now we’ve got the third ingredient (upstream blocking) sprinkled with a potent and locked in cold air mass and we’ve got ourselves a recipe for a strong late season winter storm.

Scenarios/Uncertainty

Alright, we’ve got the setup, now we want to know what could (or could not) happen. First, a disclaimer and a note about uncertainty. Without going into a deep discussion on weather model dynamics, it should be stated that not all weather patterns are created equally. What does that mean? It means that we can actually assign a percentage to how “well-behaved” or accurate a forecast will be based on the predictability of a pattern. We measure predictability in terms of model spread or how much disagreement there is between different models and their associated ensembles. Perhaps I can best sum this up with a single tweet.

0-24" sounds reasonable. 06Z GEFS plumes… https://t.co/BWQIcArf5s pic.twitter.com/EmJuARwnup

— Tony (@whatdoweseehere) March 10, 2017

Out of 21 different scenarios from just one run of the american GFS, Dulles could get anywhere from 0 to 24 inches of snow by Wednesday morning. Safe to say there is high uncertainty with this pattern. Having said that….we can break down all of the possible outcomes really by just one variable.

The Chosen One (Variable)

Location, location, location. Did I mention location? Things need to line up just right to get a March mid-Atlantic blockbuster snowstorm. Honestly, things need to line up well just to get any snow around here in March. But despite the date on the calendar, the signals for a big snowstorm are there. We’ve got the cold air in place. We’ve got a blocking high pressure. Heck, we even have anomalously warm sea surface temperatures along the east coast that will serve as fuel for a strengthening storm. What we don’t have is a solid idea of where these two storms will merge or “phase” to create the huge snowstorm we all desire.

If they combine too late, like our Canadian friends depict in their most recent model output, we would only get a glancing blow. Sure, it will be cold enough for snow, but it would still be a huge disappointment considering the likely large amount of dry air wrapped around the system that would dramatically reduce snowfall totals around here. Under this scenario, the best we could hope for in the DC/Baltimore area would be 2-4 inches, with higher amounts towards the coast and the northeast.

Canadian model forecasted surface pressure and precipitation type from Monday night through Tuesday evening. (Via Tropical Tidbits)

But there is such a thing as too soon. A late phasing of these storms would at least bring us some snow. Should the two systems decide to combine forces a bit too early like this afternoon’s American model output, we are likely left with a mixed bag of precipitation, most of which will be a cold rain. Lets call it a slushy 1-3 inches that barely sticks onto anything but the grass and cars.

I give you permission to root against American in this case. (Via Tropical Tidbits)

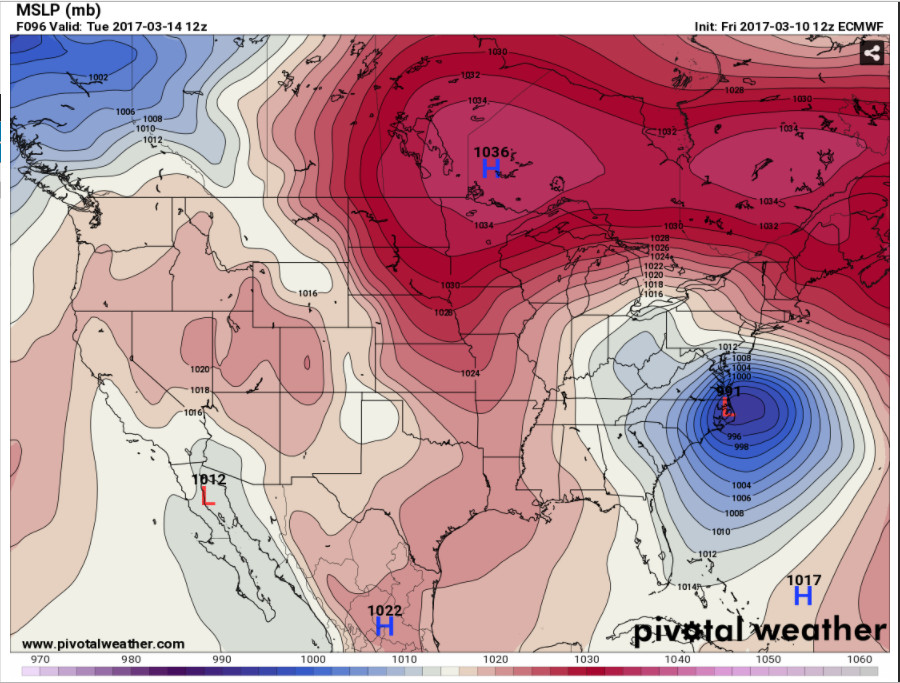

So what is our Goldilocks scenario? The one where we get the phasing jussst right? Well, in what amounts to a huge buzz kill, I can’t show you any animation. Not because it doesn’t exist. In fact, the blockbuster storm scenario is being forecast by the gold standard of weather models, the European. But their brilliance (and lots of copyright rules) prevent me from showing a detailed output from their model. I can show you this lovely screenshot of the forecasted surface pressure on Tuesday morning. You’ll see a beauty of a storm sitting over the outer banks of North Carolina, a pretty ideal position if we want some heavy snow around these parts. This scenario is not without its downfalls, as a storm track this close to the coast would result in a changeover at some point, but not before a significant amount of snow fell. We’ll call this one our widespread 6+ inches scenario.

European forecast surface pressure for Tuesday morning. (Via Pivotal Weather)

So whats our forecast?

I suppose we should end this post with an official prediction. As of right now, I am leaning towards the first scenario, the one where we get a glancing blow by a developing storm. There is little doubt that a huge storm will “bomb” out along the east coast early next week. But it feels to me like that first system will start moving again a bit sooner than forecast, giving us a late phase scenario. Additionally, storms undergoing such rapid intensification will undoubtedly wrap some dry air around the backside. You can see this pretty well in the precipitation holes form the model scenarios above. Simply put, we want to be in the path of a near peak strength storm rather than in the path of a storm still getting its act together.

I hope I am wrong. And given the high uncertainty with the pattern, there is a good chance I am.