Here we go again. Like clockwork, we’ve reached the end of August and once again, the Atlantic basin has come to life with flurry of tropical activity. Despite the expected uptick in tropical activity around this time of year, you’ve likely heard recent stories about the hurricane “drought” currently going on the east coast, with a major (category 3 or higher) hurricane having not made landfall in over 10 years. Even more impressive, the typically hurricane prone state of Florida hasn’t had a major hurricane make a direct hit since 2005. But could both of these streaks end by early next week?

While the upcoming forecast of this piece of energy (an ugly and unorganized piece of energy at that!) may seem like benign, a closer look reveals the true stakes at play. It’s another round in the ongoing battle for supremacy in the world of weather modeling: The American GFS versus the European EMCWF.

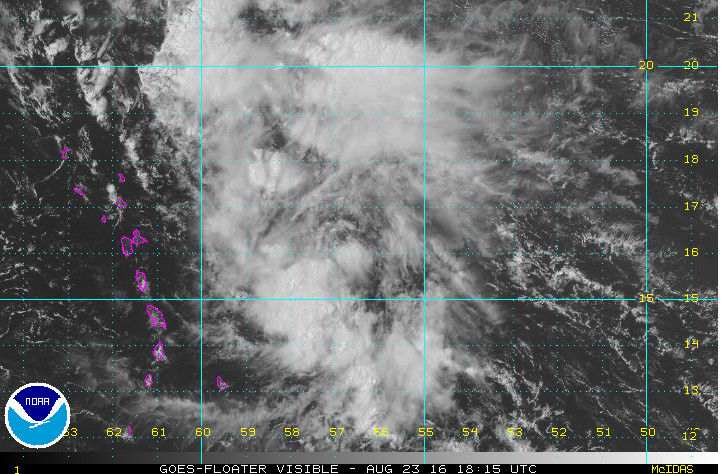

Invest 99L looks pretty messy right now. Via NOAA SSD

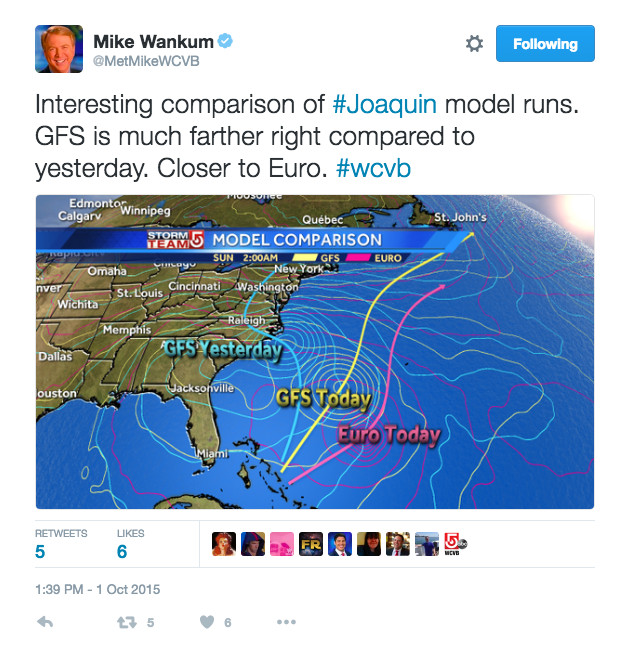

This is certainly not the first battle between these two heavy weights. In fact, a similar stand-off took place in the exact same arena last year with the infamous hurricane Joaquin. You might recall the bevy of criticism lobbed against the American model after then European model correctly forecast the intensity and eventual out to sea path of Joaquin, while the American model held onto an east coast landfall solution for several runs.

Of course, this all came on the heels of what was very likely the first public spout between the two models, hurricane Sandy. Here, once again, the European model scooped the American model by whopping 6 days, correctly forecasting an abrupt left turn the storm, taking Sandy into the NYC/NJ region. The outcry was so large from this public embarrassment that the call for reform made it all the way to Congress (this is back when Congress actually passed bills), where some 207 million dollars was earmarked for upgrades to the weather infrastructure, which included forecasting model improvements.

And those improvements have been happening. In May, the National Center for Environmental Prediction went operational with the new and improved GFS. Amongst several crucial improvements was the inclusion of a new data assimilation algorithm that will enable the American model to utilize weather observations to make corrections to model forecast output, something the European model had been doing (and some suspect the main cause for its dominance over the American model) for several years. I would also be remissed if I didn’t mention the crucial role that some of our very own University of Maryland AOSC faculty played in the implementation of the upgraded GFS.

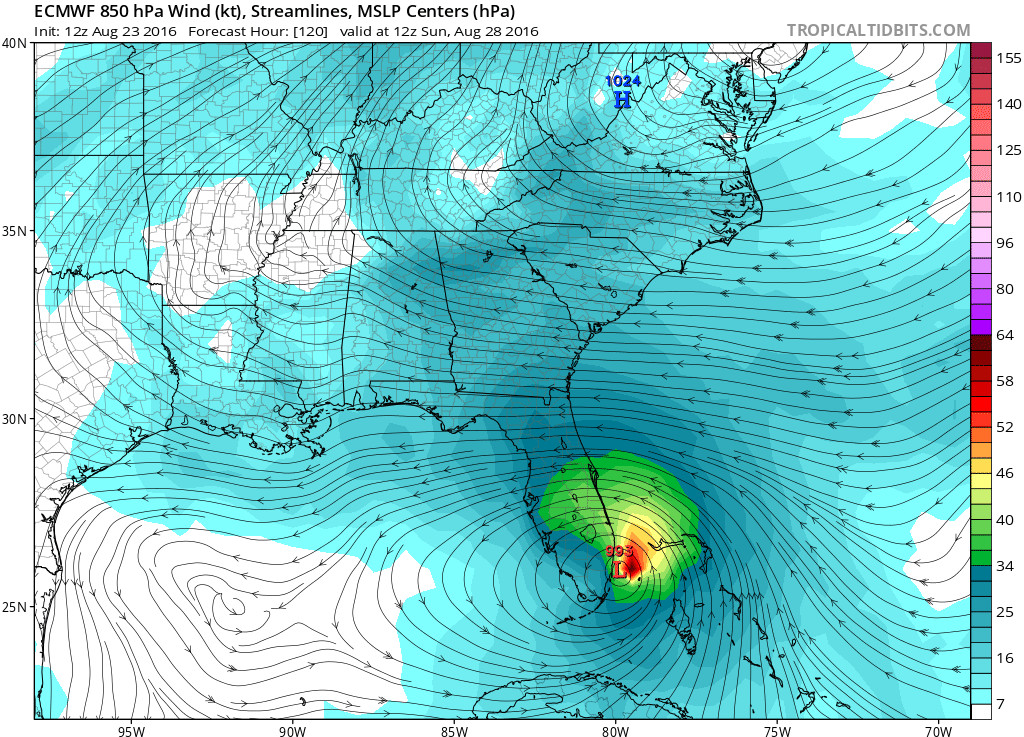

But all of this is old news. The real story here is the next round in this fight, a fight that started to take shape with todays model guidance output. The European ECWMF takes the current unorganized piece of energy, strengthens it greatly near the Bahamas and tracks it directly into south Florida on Sunday morning.

Strong hurricane makes landfall in south Florida per the ECMWF. Via Tropical Tidbits

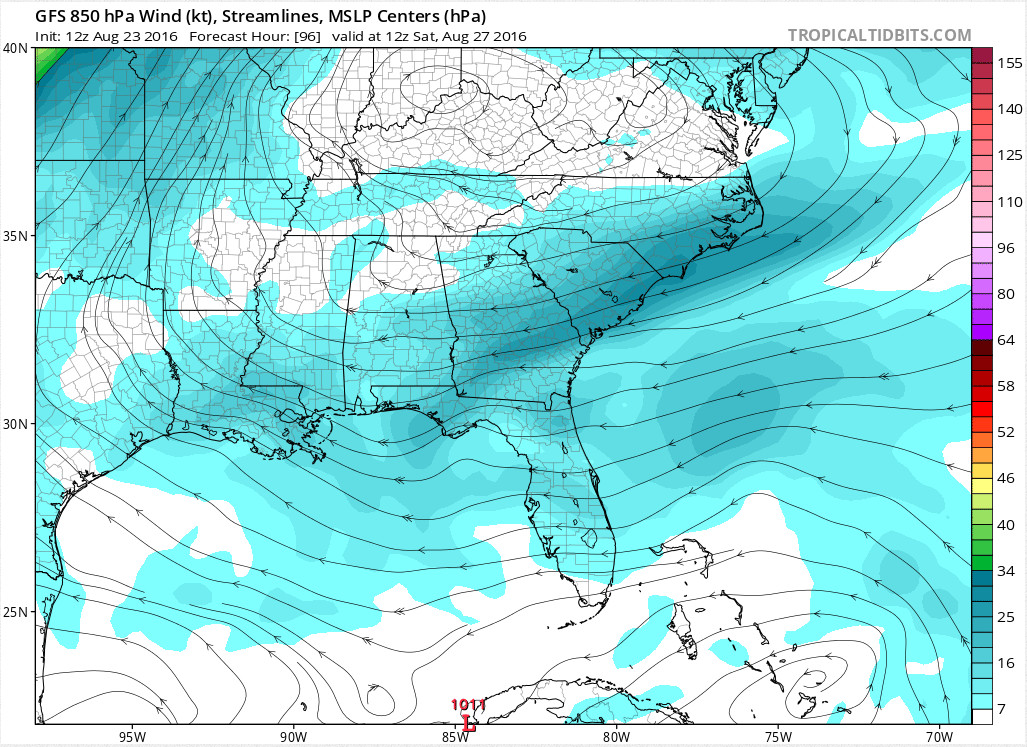

The American GFS? Well, lets just say its output doesn’t quite agree. The GFS is forecasting for the current unorganized piece of energy to remain just that, unorganized and uninteresting as it passes harmlessly south of Florida as a mere tropical disturbance.

GFS output at the same time, same place. But no hurricane….via Tropical Tidbits

We here at the UMD Weather center aren’t quite ready to throw our hat into the corner of either model. To do so at this point would be just plain silly. In fact, one of the new strengths of both of these global models is the ability for them to ingest new information and make forecast corrections on the fly. With so much time between now and the potential landfall, this forecast will change again. Of course, that won’t stop the current whispering from growing into a loud a public debate about the merits of one model versus the other. We will take the wait and see approach for now.