Scanning the various weather maps, he quickly analyzes and makes sense of the ensemble forecasts and satellite imagery that lies before him. The confluence of shaded Doppler shapes and contoured isobars is skillfully synthesized into a forecast. However, Capital Weather Gang forecaster Jeff Halverson knew he was missing something on July 30. That was the day rampant flooding wreaked havoc on Ellicott City.

The topographic bowl-like shape of the city has made it historically vulnerable to accumulating a massive volume of rainfall. Since 1950, seven destructive flood events have occurred in Ellicott City. “Water gets in there like a sluice,” said Halverson. “Flashfloods are as much about landscape, topography—as they are about rain. It’s truly multidisciplinary.” This flooding event like its ancestors caught forecasters off-guard in its sudden severity. As Halverson points out in one of his Washington Post articles, “Flash flood warning essentially becomes a now-casting exercise.”

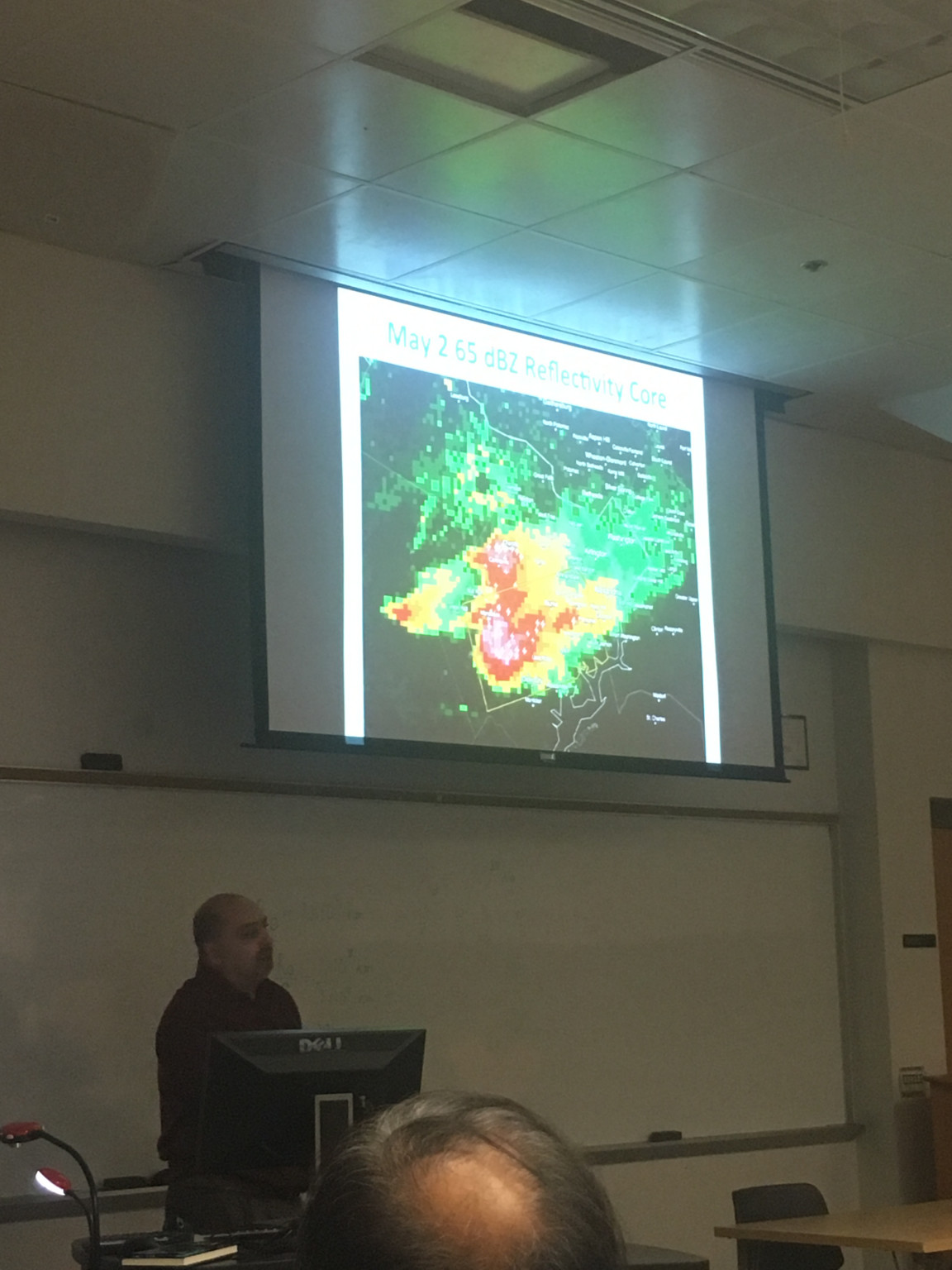

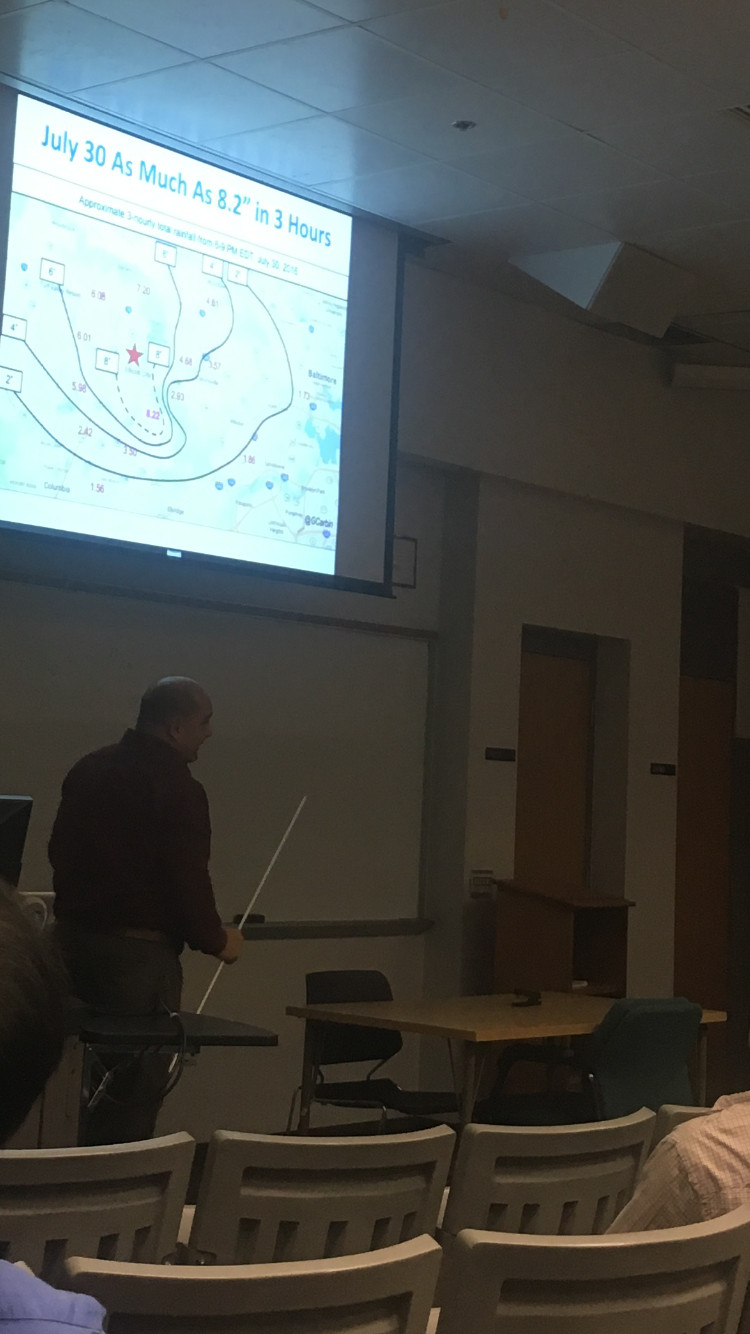

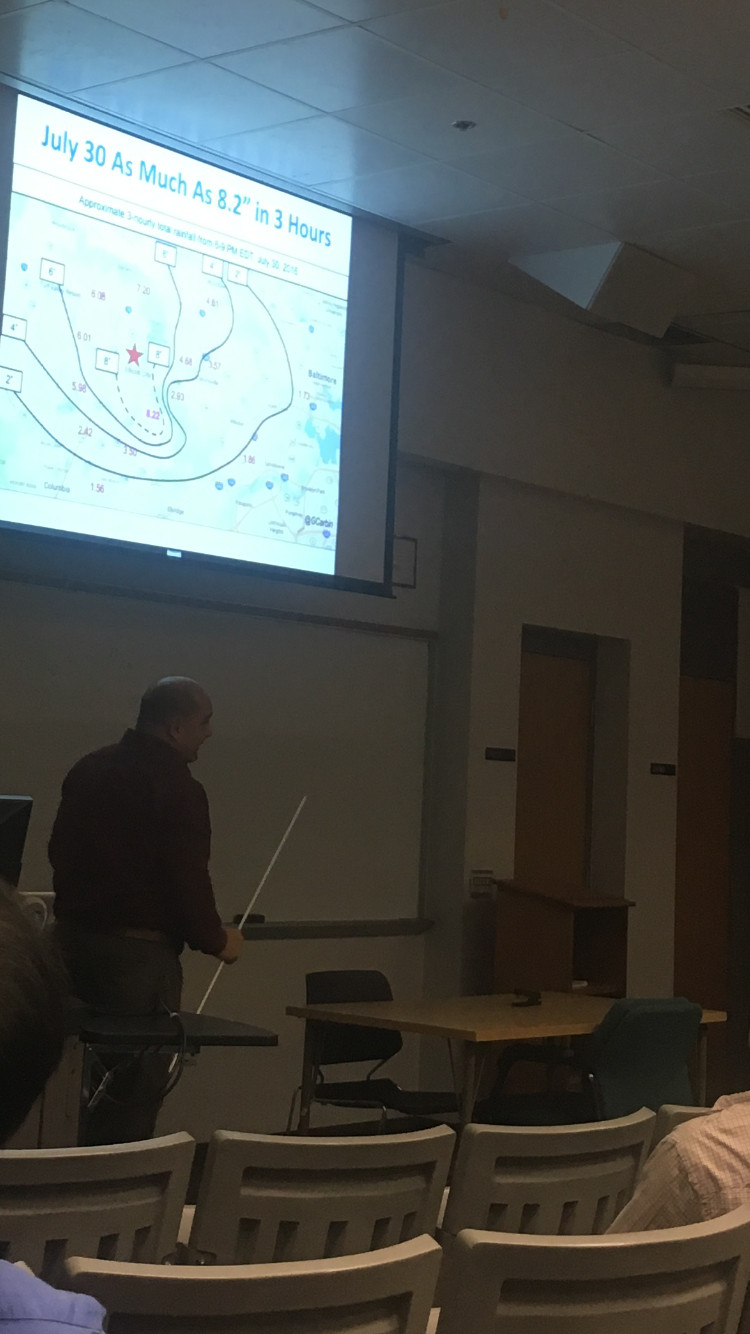

“All that time I wish I had caught it,” said Halverson, who had consulted a variety of synoptic maps that morning to try to give better lead-time on the storm. “I thought perhaps I hadn’t looked at the water vapor imagery—but no it was still dry.” Eventually around 3 p.m., the Capital Weather Gang was able to observe echo training in the radar that indicated the potential for rapid development of a quasi-stationary, mesoscale thunderstorm. But the massive destruction that ensued from the concentrated 8.2 inches of rainfall still was unable to be foreseen by even the highest resolution of models.

Jeff Halverson came to speak to faculty and students at University of Maryland to discuss other severe summer weather events that happened in the D.C. area during the preceding summer. A common theme amongst these convective super-cell days was the shear uncertainty surrounding their progression.

“What we need to do is get better at conveying uncertainty,” said Halverson, “The models are great but we have to their limitations.” The trend of ‘fake news’ proliferating on social media has been a hot-button issue for political news outlets, but weather forecasters have had to deal with the spreading of such rumors since the dawn of social media. “Someone will put on Facebook, ‘Snowmaggedon’ at 10 days out,” said Halverson, “So then we have to look at the ensembles too early on and do damage control way too early on.”

Halverson thinks packaging the ensembles in a way the public can understand will be crucial towards enhancing the publics’ understanding of severe weather events and their level of imminence. He discussed the importance of the National Weather Service’s social science research into people’s perceptions of warnings versus watches that are issued. “People aren’t taking for example, tornado watches, at face value,” said Halverson, “They are fatigued.”

As we move into the more snow-laden months of January and February, it will be interesting to see if weather forecasters will be able to come to a consensus with the public with what is certain and what is uncertain. Even if snow does not factor in, the predictions for any precipitation event may be put increasingly to the test.

“Heavy rain events may be increasing because of global warming,” said Halverson, “The line between climate and weather may be fuzzier than we once thought.”